US-China tech war: Huawei is still on the hook as Joe Biden fine-tunes America’s competitive strategy with Beijing

- The US Innovation and Competition Act earmarked US$54.2 billion towards shoring up America’s competence on a number of technological fronts, including chips production, and catch up on 5G technology

- It also leaves Huawei on a list of restricted entities, banning it from gaining access to US hardware and software until it can prove that it no longer poses any threat to US national security

In the second of a five-part series on US-China technology policies under the Biden administration, Pan Che, Xue Yujie and Celia Chen take a look at how Huawei Technologies – the very first to come into the policy cross hairs of the former Trump administration – has fared nearly six months under the new regime, and what this says about the future of US-China relations over technology. The first part is here.

US officials have gradually upped the pressure on Huawei since as early as 2012, accusing the company of being a national security risk because of alleged ties with China’s military and security agencies.

Huawei has not been that lucky though. On December 1, 2018 Meng was arrested in Canada while transferring planes at the Vancouver airport, at the request of the US government. By May 2019, Huawei’s fate was sealed when the Commerce Department added Huawei and 70 affiliates to its Entity List, banning the telecoms giant from buying parts and components from US companies without US government approval.

Then US Commerce Secretary Wilbur Ross said at the time that Trump backed a decision that would “prevent American technology from being used by foreign owned entities in ways that potentially undermine US national security or foreign policy interests”.

In the following months more pressure was added until a variety of loopholes were closed in August 2020, cutting Huawei off completely from buying any chips made with US equipment or software. This included chips from leading foundry Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company (TSMC) – which had been making chips for HiSilicon, Huawei’s in-house chip design unit.

Eric Xu Zhijun, a rotating chairman at Huawei, said earlier this year that Huawei could no longer find any chip manufacturer to make chips for it. Meanwhile, as of June 2021, Meng’s extradition case is still ongoing, a sign of the continued struggle of the firm as a whole.

For analysts, Huawei’s future remains gloomy amid the US chip blockade and amid uncertainty as the company transforms from a pure hardware provider into a software services company, including cloud and its own Harmony operating system.

“The moves to electric vehicle systems and now major software development seem to be more of a response to government expectations rather than business demands or market necessities,” said Brock Silvers, chief investment officer at Hong Kong-based Kaiyuan Capital. “Both efforts are far from Huawei’s core, and any success is far from assured.”

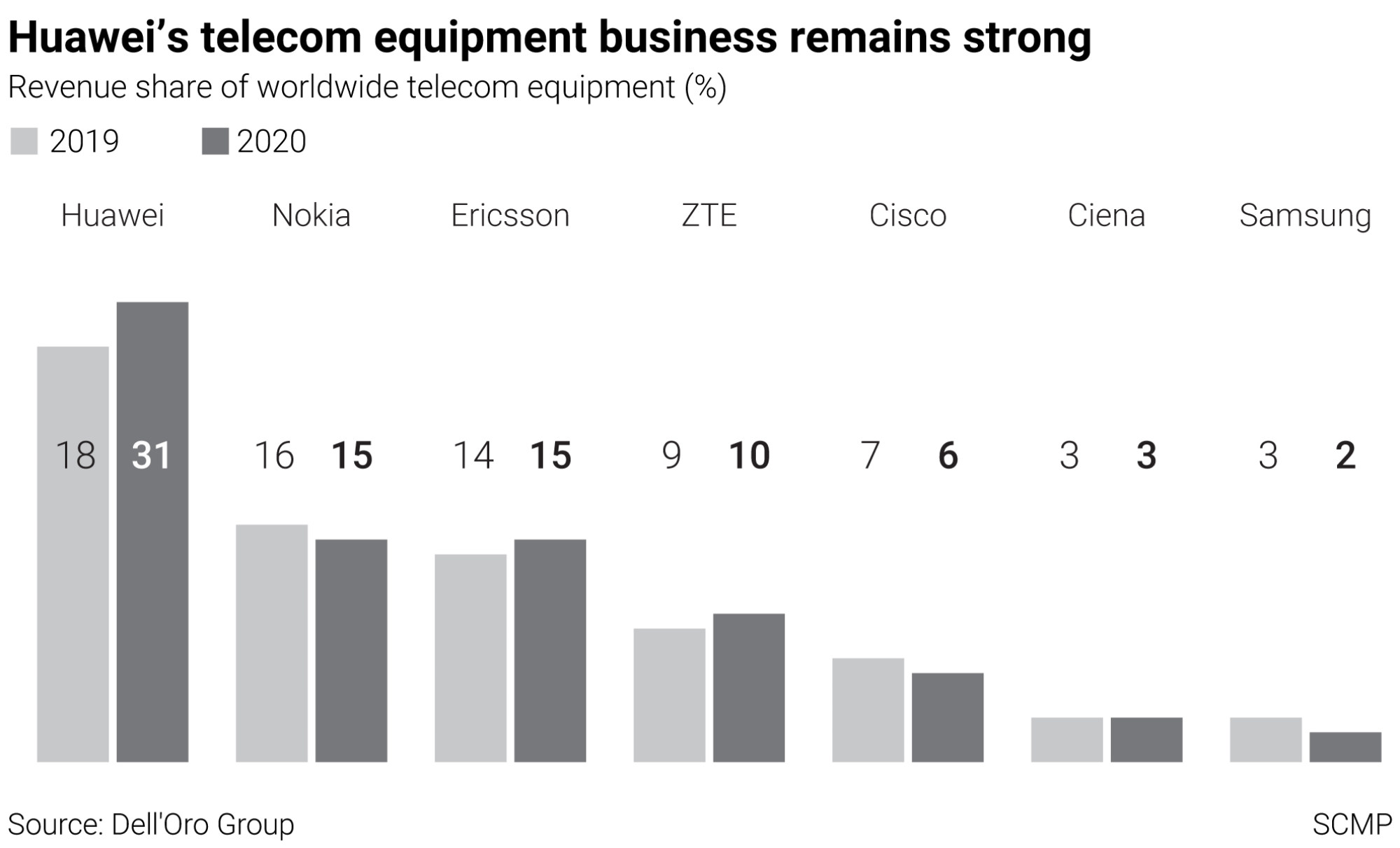

Its core telecoms equipment market is also feeling the strain, as an increasing number of foreign governments and carriers follow strong advice from the US to exclude Huawei from their telecoms networks on security concerns.

Huawei, still a private company, has maintained revenue growth but growth has now slowed to the lowest rate on record.

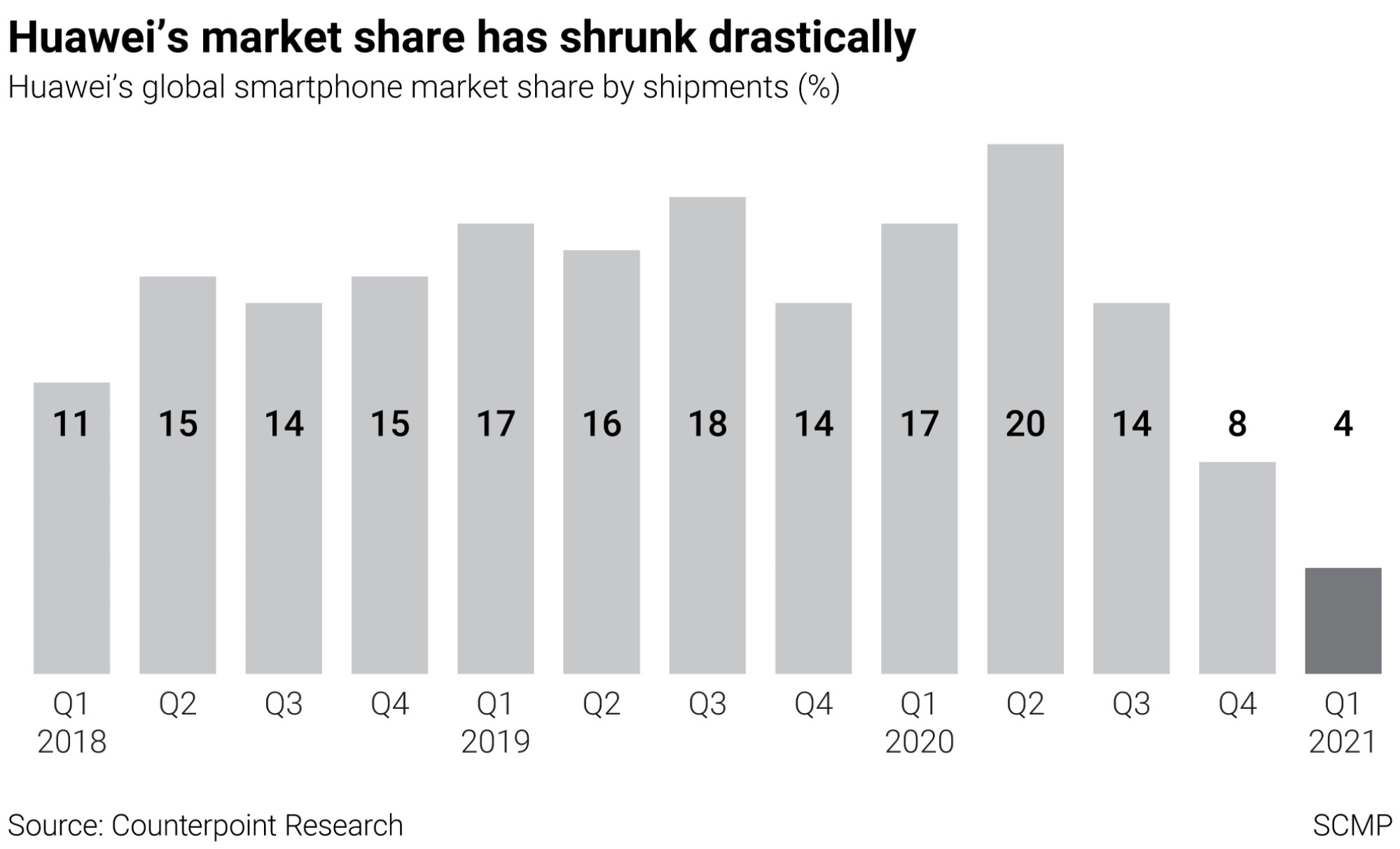

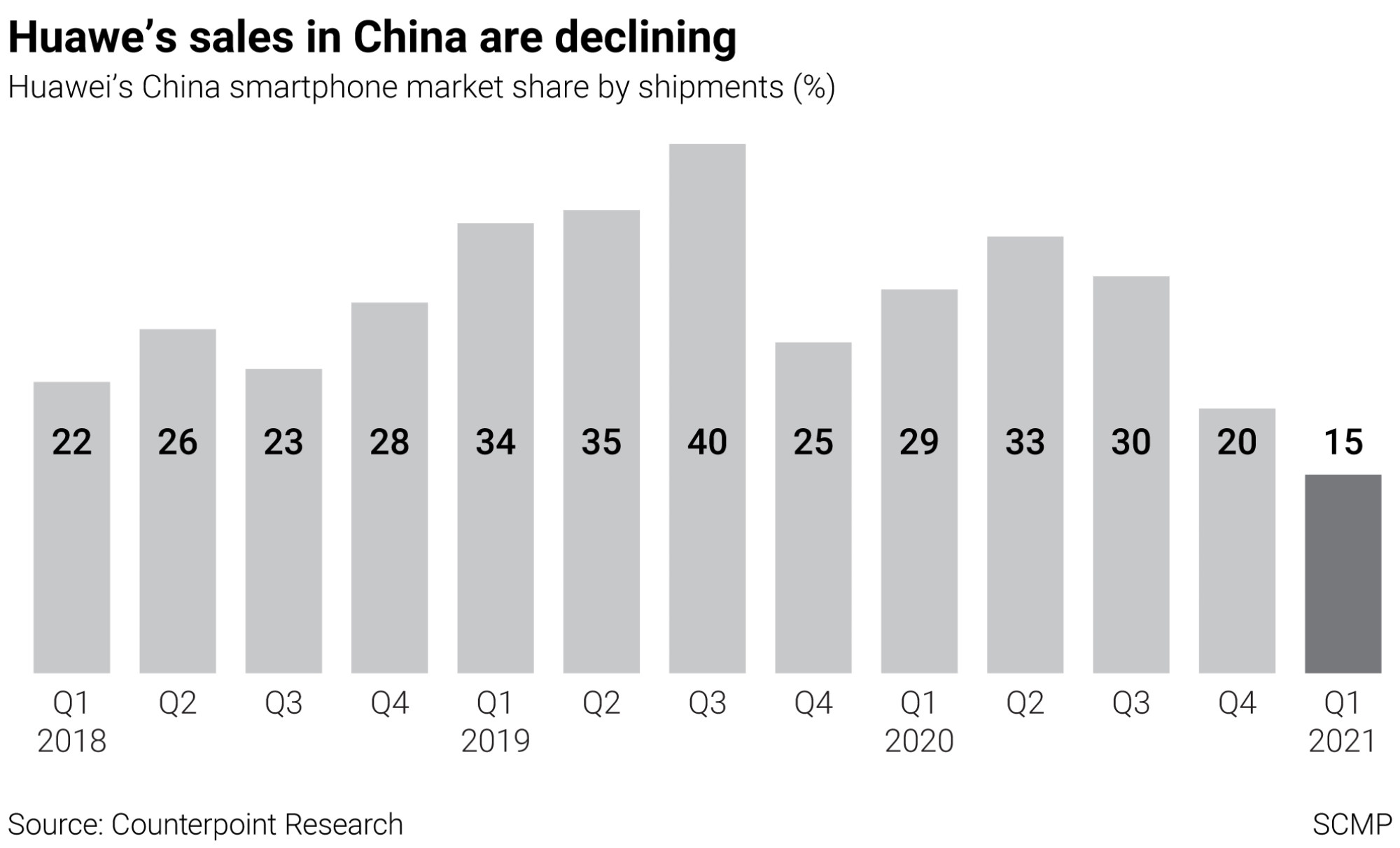

This is in sharp contrast to five and half years ago when Richard Yu said Huawei would one day beat Samsung and Apple to become the world’s biggest handset maker. Few at the time doubted the optimism of the then head of consumer electronics at the Chinese technology giant.

However, analysts said it will be a long shot for Huawei to make money from Harmony.

“Huawei may not find significant demand [outside China] for a China-controlled version of an android phone that lacks any Google services or apps. The appeal seems limited,” said Silvers, adding that many tech giants from Microsoft to Samsung had tried to take on Android but failed, and Huawei “doesn’t have much of a track record in terms of software development”.

Huawei has to focus on building its HarmonyOS user base and partnerships with other electronics brands and carmakers “as it will help to establish its bargaining power and showcase its super device capability,” said Will Wong, a Singapore-based analyst at tech research firm IDC.

But the initial list of partners for Harmony are more about home appliances manufacturers, such as Midea and Skyworth, with no Chinese smartphone makers on board yet.

Analysts say Huawei’s struggles have exposed China’s disadvantaged position in technology despite ownership of “the world’s most comprehensive industrial production system”, a predicament President Xi Jinping has likened to having one’s neck at the mercy of an opponent’s hand.

As things stand, American suppliers dominate the entire global semiconductor supply chain. US companies control more than 70 per cent of electronic design automation (EDA) software and core IP, while taking 41 per cent and 11 per cent global shares in semiconductor equipment and materials respectively, according to data from a joint report by Boston Consulting Group and Semiconductor Industry Association.

To survive, Huawei will have to ramp up investment in chip manufacturing and chip plant equipment, such as lithography, which some industry watchers have said would be akin to “Huawei deciding to open a restaurant, and then having to make its own kitchenware and tables.”

A former engineer at NAURA Technology Group, a leading Chinese semiconductor equipment maker, said China is unlikely to catch up in areas such as lithography in the coming years. He requested anonymity due to the sensitive nature of the subject.

But the bottom line appears to be that unless and until the US and China can resolve their tech rivalry – and some analysts think this will never happen – Huawei will remain in Washington’s cross hairs.

“Given that the US intends to restrict Huawei’s development in high-end areas such as 5G … the probability of the US lifting its ban on smartphone chips for Huawei in the short term is scant,” said Arisa Liu, a chip industry analyst with the Taiwan Institute of Economic Research.

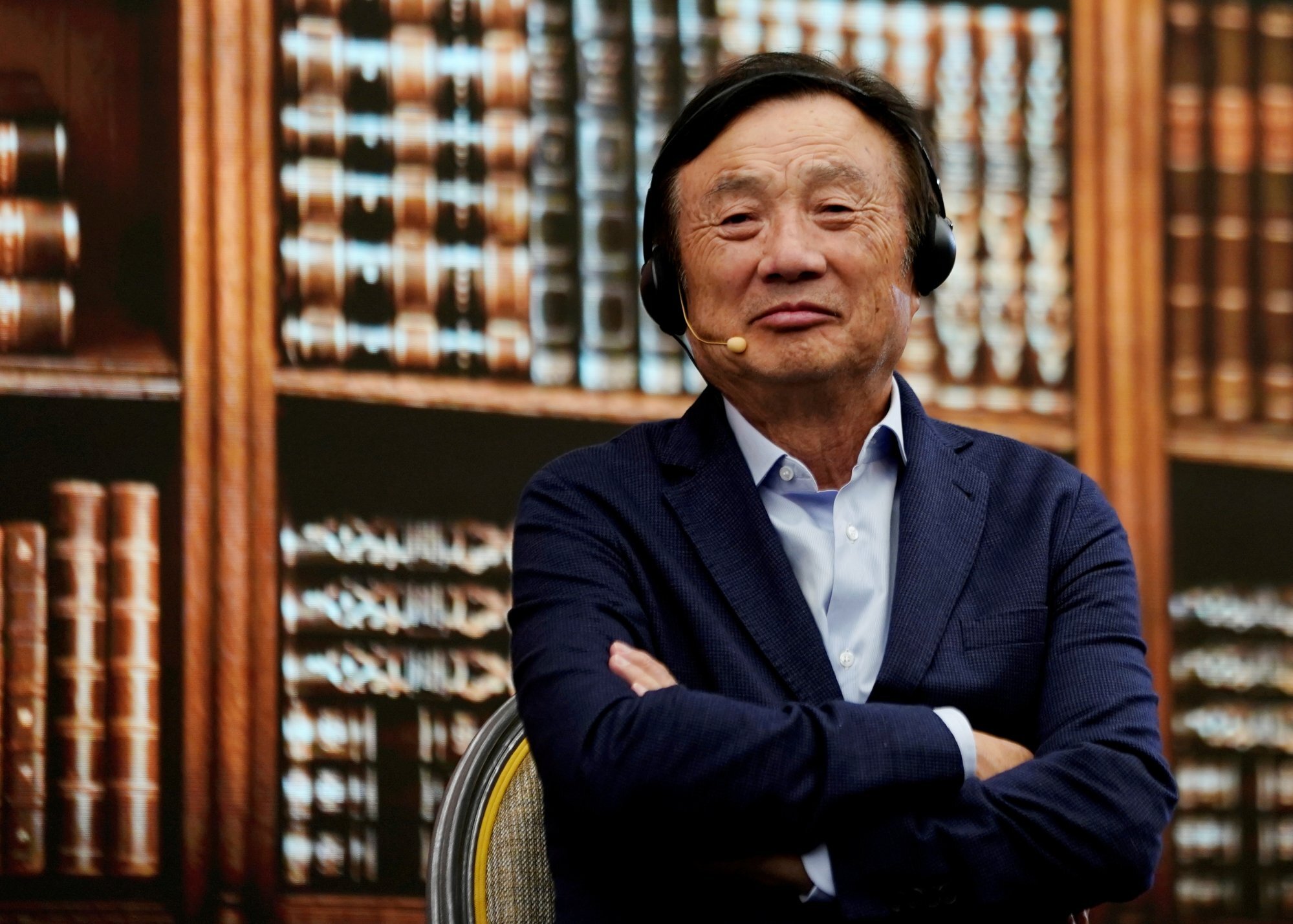

Even Huawei’s founder Ren said earlier this year that he thinks it would be “extremely difficult to remove Huawei from the entity list” and the goal for Huawei is simply “to survive” after it reported its lowest revenue growth in a decade.

For other big Chinese tech firms, one clear takeaway from the Huawei story is to avoid incurring the wrath of Washington if at all possible.

“In the long term, we are likely to see continuity in terms of Trump’s efforts to reshore semiconductor manufacturing to the US, and hopefully intensify it,” said Will Hunt, a research analyst at the Centre for Security and Emerging Technology, a think tank at Georgetown University.